My brother John Middendorf died suddenly on June 21, 2024. It has been three months, which seems unreal to me. Hasn’t it been an eternity? Then again, it feels like yesterday—or that it never happened at all. How could someone so alive now be dead? Losing him has felt like a ripping out of something central in my core. Until he was gone, I didn’t realize how intrinsic he was to my sense of self.

I grew up as the middle child of five. There were three years between my first and second sister, and a gap of seven years between my two younger brothers, but the three of us in the middle were clustered together: Martha born in 1957, me in 1958 and John in 1959. “Stairsteps,” as some people call it.

The Middle Stairstep

I loved being The Middle Stairstep. The three of us looked out for each other. I don’t remember spending much time alone during childhood. With one sibling slightly older and one slightly younger, I always had a playmate.

When John was 14 years old, he started climbing rocks. It became a passion, much to my mother’s dismay. She knew hanging onto a lip of the near-vertical cliff, hundreds of feet above the ground, attached to a rope attached to a piton wedged in a crack in the rockface was, well, risky. With the obliviousness of youth, I had no such fear. John was just doing what he loved, and I was happy that he was happy.

Then Martha, The Oldest Stairstep, who had suffered with epilepsy since she was five, died suddenly of a particularly bad seizure just four days shy of her 22nd birthday. Nobody imagined she would die. I plunged into grief—it really did feel like drowning. It was my first experience with a massive loss, and I felt physical pain in my chest—a dull ache—for months.

As the pain slowly faded, I became ever more aware that my brother was hanging off the sides of cliffs. He could fall. If he fell, he would die. If he died, I would be in agony once again. I didn’t want to lose another sibling—I never wanted to hurt that much again. I know that sounds like I was only thinking of my own potential pain, and I guess that is because I was. His pleasure was pushing himself to the edge of what was possible. Yet, his pleasure was my burden.

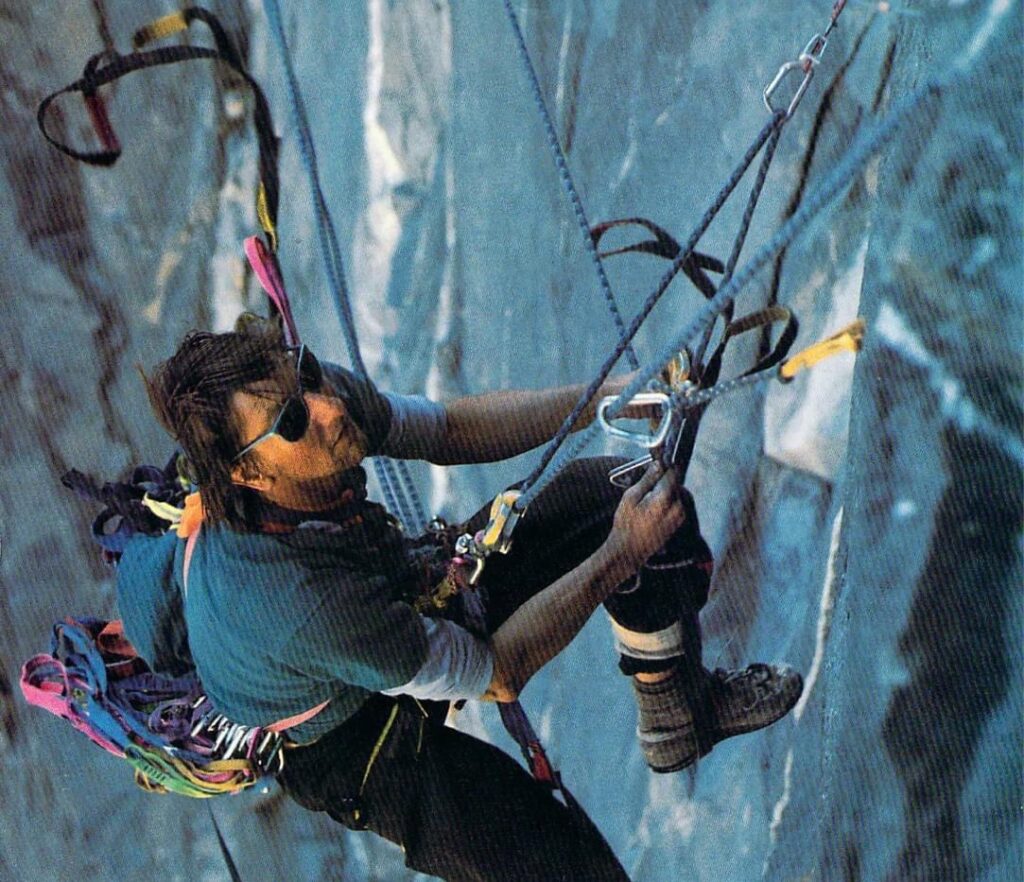

But what could I do? My mother’s pleading with John to take fewer risks in his climbing seemed to have the opposite effect. John was becoming a world-class climber, creating new and challenging routes on some of the world’s steepest and tallest granite walls.

He could have died so many times and in so many ways. Almost never did I hear about a climb he made until afterward, when he was back on level ground. This was a kindness on his part, because not knowing greatly benefited my mental health. It was hard enough hearing about his climbs afterward.

Two perilous climbs stand out.

In March 1986, he was living in “Camp 4” in Yosemite Valley as part of the Search and Rescue Team, that is, as an experienced climber who the National Park Service could call upon to reach any park visitor who needed rescuing. Sadly, that sometimes meant retrieving bodies, for there are plenty of dangerous hikes in Yosemite. The rescue team put his climbing skills to use, but its main advantage was having permission to live long-term in the Valley, sometimes in a tent, and sometimes in a non-functional VW bus.

Half Dome

John had lived there close to three years that March. Most days were spent planning a climb, climbing, or resting after a climb. Two friends invited John to join them to climb a 2,000-foot wall, the South Face of Half Dome. It was late winter, but the weather was clear, and all the weather predictions being broadcasted said it would stay that way. Four days in, they were only one day from completing it when a severe winter storm blew in with snow and freezing rain that froze all their equipment to the rock face. Moving from their location was impossible. Their portaledges, which allowed them to sleep on the wall, were entirely inadequate, twisting and needing constant adjusting. One collapsed entirely. Three utterly miserable days later, they were rescued by helicopter during a brief break in the weather. They wouldn’t have lasted much longer.

John wrote about that rescue for Climbing magazine in 1990, and I ghostwrote the story (for John) for Guideposts in May 2000. The experience transformed John—for the better. He was kinder, more people-focused and confident there was a God who loved him. During those three days, while shivering and wrestling with his flimsy portaledge, he used his brilliant mind, trained in engineering at Stanford, to mentally design a better portaledge. For the next 10 years he produced sturdier portaledges with better materials, as well as heaps of other climbing equipment, and sold them through his company A5. His new design enabled multi-day climbs that had never been possible before.

Great Trango Tower

In 1992, he and another friend, Xaver Bongard, made the first successful climb of the Great Trango Tower, a 4,400-foot rock face in Pakistan. I say first “successful” climb because every member of the Norwegian team who climbed it in 1984 died in the descent. Nobody has climbed it since John and Xaver. The reason? Terrible weather, repeated ice and snow avalanches, and multiple rockfalls (some as large as refrigerators). John was 32 and at peak physical prowess, yet his life could have been extinguished hundreds of times in the 16 days of climbing and the two days of rappelling in descent. I believe God protected him, and so did our mother, a faithful woman of prayer. John knew he had been spared.

Over the next 10 years John climbed less often. He built up his A5 company, sold it to The North Face, then worked as a Colorado River guide at the Grand Canyon. It seemed to me he was taking fewer risks, deeming his life more precious. Or was I just projecting my own desires?

When he was approaching 40, I asked him about it. “So, John, no more first ascents with avalanches and falling rocks?” He grimaced a bit. “I’ve lost a lot of friends,” he said. “After 40, a person’s body just doesn’t perform at a top level anymore. You think you can do something because you’ve always been able to do it, but then when the critical moment comes….” His voice trailed off.

At that point I had three rambunctious kids who adored him. Sometimes I caught him looking at them wistfully. “You’d be a great dad,” I said. He looked at me sideways, the way he did, and smiled.

And then came the momentous, glorious day when our family met Jeni, who was a fellow river guide and was so obviously his match in every way. Marrying her calmed his soul, accentuated by the birth of Rowen and Remi, 17 and 11 years ago. For the last 16 years they’ve lived in Australia, where there are plenty of opportunities for outdoor adventures—but no longer did he push himself to the edge of what was possible. Instead, he developed himself as a person—using his flexible brain to become a math and science teacher, to perfect the portaledge and to write books and copious articles on the history and techniques of climbing. He generously shared what he had—time, energy, resources—starting with his family, and extending to just about anyone. He was a gentle and deliberate father, involving himself in whatever interested his kids.

He was happy. His family was happy. I was happy. No longer did I fear losing him to a loose rock or a freak storm. He was safe on terra firma, seemingly healthy at age 64, loving his wife, wanting to raise his kids. He was valuing his life as much as I valued it. I love him for that.

Then, in the early hours of June 21, he had a massive event. He never woke up, though Jeni and I did CPR until the ambulance arrived. And since then—the waves of grief.

John was someone who intuitively understood me, and I him. Before he died, I could not envision a world in which he was not alive. Yet—in a moment—he was gone.

Writing this tribute to him has been painstakingly slow, the slowest piece of writing I’ve ever done. I’ve stared at the computer screen for an hour at a time before writing the next sentence. It’s as if putting John into words was the way for his death to become real, a moving forward through the drudgery of grief. With each word, the bleak truth that he is gone does indeed feel more real.

For me, this summer has been an answer to the prayer of the psalmist:

“Teach us to realize the brevity of life, so that we may grow in wisdom”

(Psalm 90:12, NLT).

Three months of thoughtful reflection later, I’m now utterly convinced of the brevity of life. Life is fragile and precious. People deserve my time. Every minute counts.

And so, perhaps, I hope, I am one step farther along the road toward wisdom.