The first time I ever heard of a lobotomy was in the early 1980s. I was a medical student, but I didn’t learn about it in class. Instead, I was in a darkened room with a bunch of other family members, watching a family home movie filmed 30 years earlier. The scene was some kind of a garden party, and in the midst of the lively antics of my parents, their siblings and my great-aunts and great-uncles, there was a late middle-aged woman who just…stood there. Eventually someone took her arm and led her to a chair where she just…sat there. Completely still, no facial expression, no interaction with anyone else.

The first time I ever heard of a lobotomy was in the early 1980s. I was a medical student, but I didn’t learn about it in class. Instead, I was in a darkened room with a bunch of other family members, watching a family home movie filmed 30 years earlier. The scene was some kind of a garden party, and in the midst of the lively antics of my parents, their siblings and my great-aunts and great-uncles, there was a late middle-aged woman who just…stood there. Eventually someone took her arm and led her to a chair where she just…sat there. Completely still, no facial expression, no interaction with anyone else.

I turned to my aunt, and whispered, “Who is that? What is wrong with her?”

“I’ll tell you later,” she replied, with a knowing nod.

It turns out she was my great-aunt Muriel, who’d had a lobotomy a decade before that garden party. She had been committed to an asylum in 1942 for being “unable to manage her affairs by reason of lunacy.” The exact nature of that “lunacy” is lost to history, but family lore says she was sad and agitated due to an unfaithful husband.

At any rate, she had the misfortune of being institutionalized when prefrontal lobotomies were being pushed as the cure for mental illness. In Britain, where Muriel was hospitalized, 12,000 procedures were done by 1954. In America it was even worse—50,000 were conducted before the procedure fell out of favor in the 1960s. A total of 5,000 were performed in 1949 alone.

A lobotomy is surgery on the brain to sever the prefrontal lobes from the rest of the brain. The frontal lobes are key to controlling behavior and emotions—the “executive processes,” defined as the capacity to plan, organize, initiate and self-monitor. It was the brainchild of Egas Moniz, who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine for it in 1949.

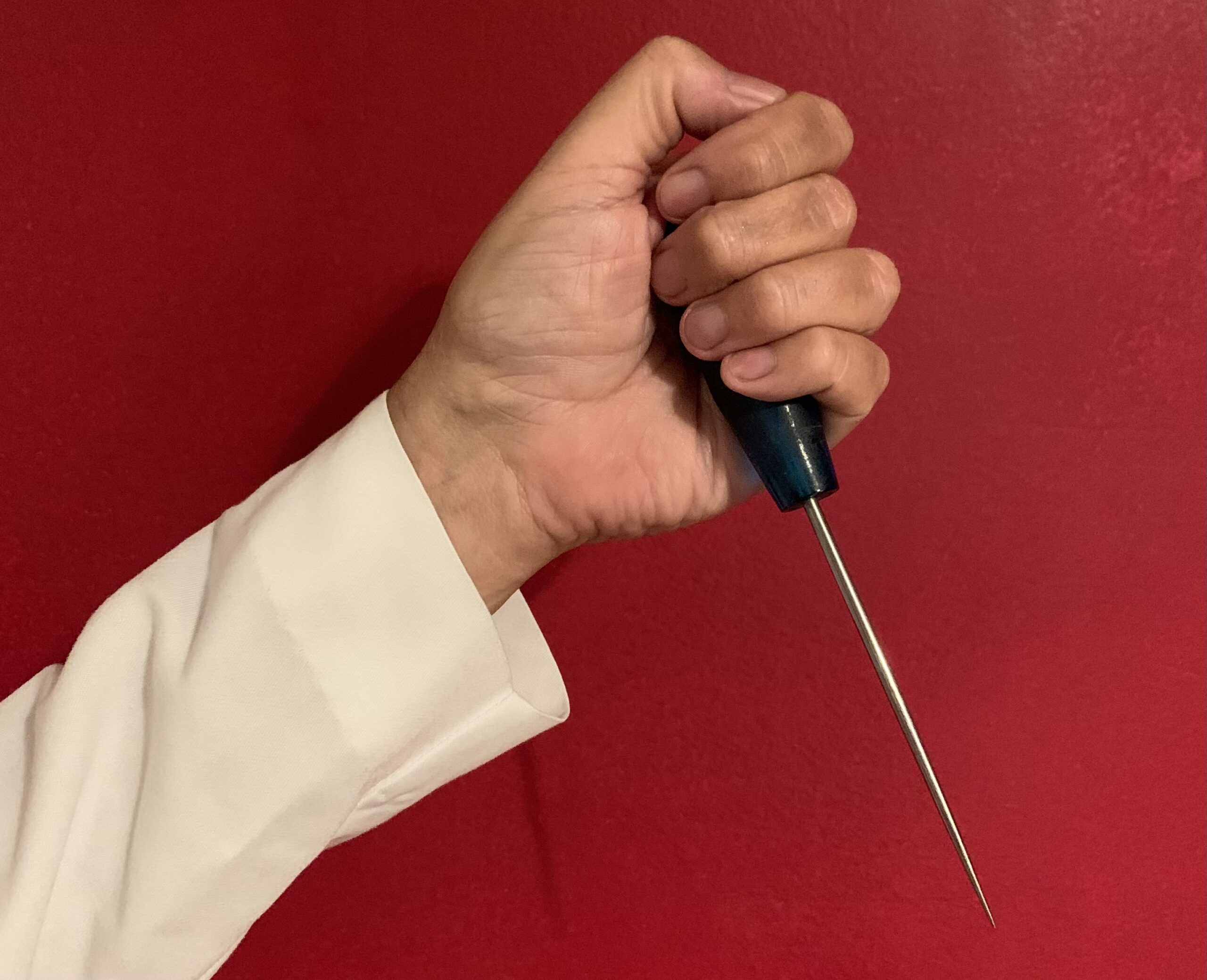

True, there weren’t effective medicines for mental illness back then, but lobotomies were an exceedingly blunt instrument. Claire Prentice has written about one of lobotomy’s biggest proponents, the neurologist Walter Freeman, who initially worked alongside a surgeon but later branched off on his own to do a quicker 15-minute transorbital procedure—using an ice pick. He wanted to empty America’s mental asylums of patients. Unfortunately, his complication rate was high, and numerous patients were left with profound mental deficiencies, some became blind or paralyzed and several died.

Who were getting these lobotomies? Mostly women. Though men outnumbered women in psychiatric hospitals, approximately 70 percent of lobotomies were performed on women. The indications for lobotomy were exceedingly broad, including schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, headaches, arthritis, “suicidal tendencies” and, in at least one 12-year-old boy, “defiance.” Tragically, he was not the youngest to receive a lobotomy.

Dr. Freeman wanted to change people’s personalities—changing them from “dangerous and aggressive” to docile and compliant. Far too often, the change was a “tragic personality disintegration,” as contemporary neurosurgeon Ernest Sachs said on page 44 in Doctor Ice Pick. For my aunt Muriel, the result was indolence and helplessness. She never initiated action. Once she was seated, she remained seated. She had to be fed and clothed, and she was essentially mute.

Other patients became disinhibited, sexually promiscuous or oblivious to social cues. Some were left incontinent, sloppy or combative. Freeman, in a never-published autobiography, acknowledged that many patients became affectless and “infantile,” but he saw this as positive, calling it a “surgically induced childhood” rendering the patient “more amenable to the social pressures under which he is supposed to exist.”

You may be wondering why the medical establishment, seeing the carnage, didn’t rise up and put a stop to this brutal operation. As early as 1950, it was banned in the Soviet Union, Germany and Japan, yet it remained the darling of the press in America throughout the 1950s. Newspaper articles of the time were overwhelmingly positive. State governments were benefiting financially, as thousands of previously uncontrolled patients who were institutionalized and draining the public coffers were post-operatively sent home for their families to care for them. Few doctors were willing to speak out.

Little by little, though, criticism of the procedure grew louder: “It was increasingly seen for what it was—a crude means of making those regarded as difficult, demanding, and dangerous patients cheaper and easier to manage,” as is written on page 49 of Doctor Ice Pick.

A prefrontal lobotomy destroyed intact brain tissue. Its purpose was to sever a part of the brain from the rest of the brain. It was widely adopted on the basis of an idea, and careful studies of outcomes had not been done. Those who spoke up against it were fighting against strong resistance, both in the medical world and in the press, who were enamored with it. Once that tissue was destroyed, it was destroyed forever.

To its proponents’ credit, at least they thought they were destroying unhealthy tissue. That is, they thought patients’ mental disturbance could be directly linked to a malformation in a certain area of the brain, the prefrontal cortex.

This is not the case with the surgeries currently being done on children with gender dysphoria. Nothing is inherently wrong with the body parts being removed. That is, a child born with two X chromosomes in each and every cell of the body has developed two ovaries, one uterus and two breasts. There is nothing defective about those body parts. Removing them is removing healthy tissue.

This is not to say gender dysphoria is not a very painful condition. It is, but the pain is an emotional pain. The agony lies somewhere in that massive web of nerves that rests under our skulls. As miserable as that pain is, I’m not suggesting we operate on the brain. Let’s not make the mistake of the lobotomists.

And let’s not remove healthy organs outside of the brain, either. But, you may protest, what if removing these organs leads to healing of the emotional pain? Wouldn’t it then be worth it? I’m not sure I would support surgery in that case, either. If the self-perception is out of step with the biological reality, then it doesn’t seem logical to me to try to adjust the body to conform with the mind. It seems much more health-affirming to treat the mind so it better correlates with the body.

It is clear the facts are lining up against “gender-affirming surgery.” True, those with gender dysphoria have a higher rate of suicidal thoughts, and of completed suicide, than those without gender dysphoria. But what is the solution? Those suicide rates dip after surgery, but they rise again to the same level a few years later (as seen here, here and here). The same level. The surgery didn’t resolve the emotional pain.

Psychotherapy is a long process and requires skilled practitioners. It is expensive and is poorly compensated by insurance companies. Surgery, on the other hand, pays well. How many children or adults who have had this kind of surgery are supported emotionally afterward? Are the surgeons arranging for counseling? And were these patients properly advised on the lifelong consequences of the surgery, that is, its irreversible nature? If they were children when they began the process, were they truly at an age and maturity level to give proper consent?

As hard as it might be to believe, it was difficult in the 1950s to raise a voice of protest against lobotomies. Likewise, it is difficult today to voice opposition to these surgeries, even (and maybe especially) when they are done on children. Transgender treatments and surgeries are the darlings of the press. Yet, as reasonable voices break through the fog, more and more people are paying attention.

The website of the American College of Pediatricians is full of helpful information, including extensive parent resources and a well-referenced article on “The Myth About Suicide and Gender Dysphoric Children.” CMDA’s Ethics Statement on Transgender Identification and a letter to the editor in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism give references and thoughtful arguments. The founder of 4thWaveNow considers herself “left-leaning” yet saw a need to bring together “a community of people who question the medicalization of gender-atypical youth.”

The families of 1,000 children and adolescents who were “rushed into treatment” at the Tavistock gender-identity clinic in London, England recently filed a class-action lawsuit, stating they “suffered life-changing and, in some cases, irreversible effects.” I predict Great Britain is only a few years ahead of us here in the U.S. There will be a flood of lawsuits in the coming years, mark my words. You heard it here first.

On page 70 of Doctor Ice Pick, Claire Prentice, writing about Walter Freeman, the wildly enthusiastic proponent of the ice pick lobotomy, concludes with a sober warning:

“Operation Ice Pick, when political power, medical orthodoxy, and an unquestioning press aligned behind a flawed man with a zealous belief in a dangerous and unproven medical procedure, should be remembered as a terrible parable of misplaced certainty and lax oversight.”

What is the best way to treat mental illness? Not with an ice pick lobotomy. What is the best way to treat gender dysphoria? Not with surgery to remove healthy organs. The future health and well-being of thousands of patients hangs in the balance.